Darlinghurst Gaol, 1841

The Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser, Thu 10 Jun 1841 [1]

COUNCIL PAPERS.

————

A Statement of the Sums appropriated by the Legislative Council, for the Service of the Year 1840, and the previous Years, remaining, on the 31st December, 1840, to be expended and charged, as being then still required, to meet the purposes for which they were appropriated.

———◦———

Hyde Park, Museum, Darlinghurst Gaol, Sydney Grammar School, Burdekin’s and Lyons’ Terraces, John Rae, painting, 1842. Image: Dixson Galleries, State Library of NSW. Reproduction: Peter de Waal

To meet arrears in the department of the Surveyor General, £1,000; towards the support of the Australian Museum, £735 2s; to meet the salary of the Colonial Agent General, £212 10s; to meet pensions payable in England, £128 12s 3d; to meet arrears in the department of the Border Police, £1,415 19s 4½d; towards forming a Circular Quay, Sydney Cove, £5,538 14s 11½d; towards building a New Government House, Sydney, £656 6s 10¼d; towards building a Library and Museum, £4,000; towards building a Strong Room for Colonial Records, and a Vault for the Treasury, £1,600; for erecting a Light House, Port Macquarie, £750; for enclosing out houses, at the Supreme Court House, £200; for draining, fencing, and other extra work for the Lunatic Asylum, £1,166 17s 7¼d; towards building the New Gaol, Darlinghurst, £3,200 7s 4¼d; towards building the New Gaol, Parramatta, £3,532 18s; towards building a Gaol, Maitland, £6,327 17s 3d; towards building a Gaol, Bathurst, £2,918 12s 8d; towards building a Court House, Queanbeyan, £1,750; to complete the Gaol at Berrima, £484 6d; towards building a Gaol and Court House, Goulburn, £7,000; for building a Watch House on the road to Bathurst, £450; towards building a Court House, Bathurst, £3,500; towards building a Court House, Butterwick, £1,600; completing a New Court House, Liverpool, £1,500; for erecting a Court and Watch Houses at Merton and Invermein, £2,559 8s; for erecting a Watch House Green Hills, £750; for erecting a Watch House, Maitland, £540; for constructing Solitary Cells at Yass, £350; for compensations to clergymen and their families, in lieu of land £320; for providing a parsonage for the Rev John Vincten, of Sutton Forest, now of Castlereagh £250; to meet arrears of salaries of Presbyterian Clergymen, £200; towards the support of schools, of the Church of England, established prior to 1837 £379 3s; in aid of the Mechanic’s Institution, Newcastle £300; to meet the half-salary of the Colonial Treasurer, (absent on leave) £657 1s 3½d; for salaries to extra clerks, in the Department of the Auditor General £108 14s 9d; for remuneration to Colonel Kenneth Snodgrass, for Colonial Services £754 15s; retired allowance to Frederick Garling, Esq, for 1840 £300—£57,127 0s 10¼d—Port Phillip.—Towards the erection of a Gaol, Melbourne £2,843 16s; towards erecting a Court-house, Melbourne £2,000; towards erecting a Watch-house, Melbourne £753; towards erecting a Watch-house, Geelong £739—£9,331 16s—— Total £63,469 16s 10¼d.~ ~ ~ ~ ~

Illustrated Sydney News, Fri 16 Nov 1866 [2]

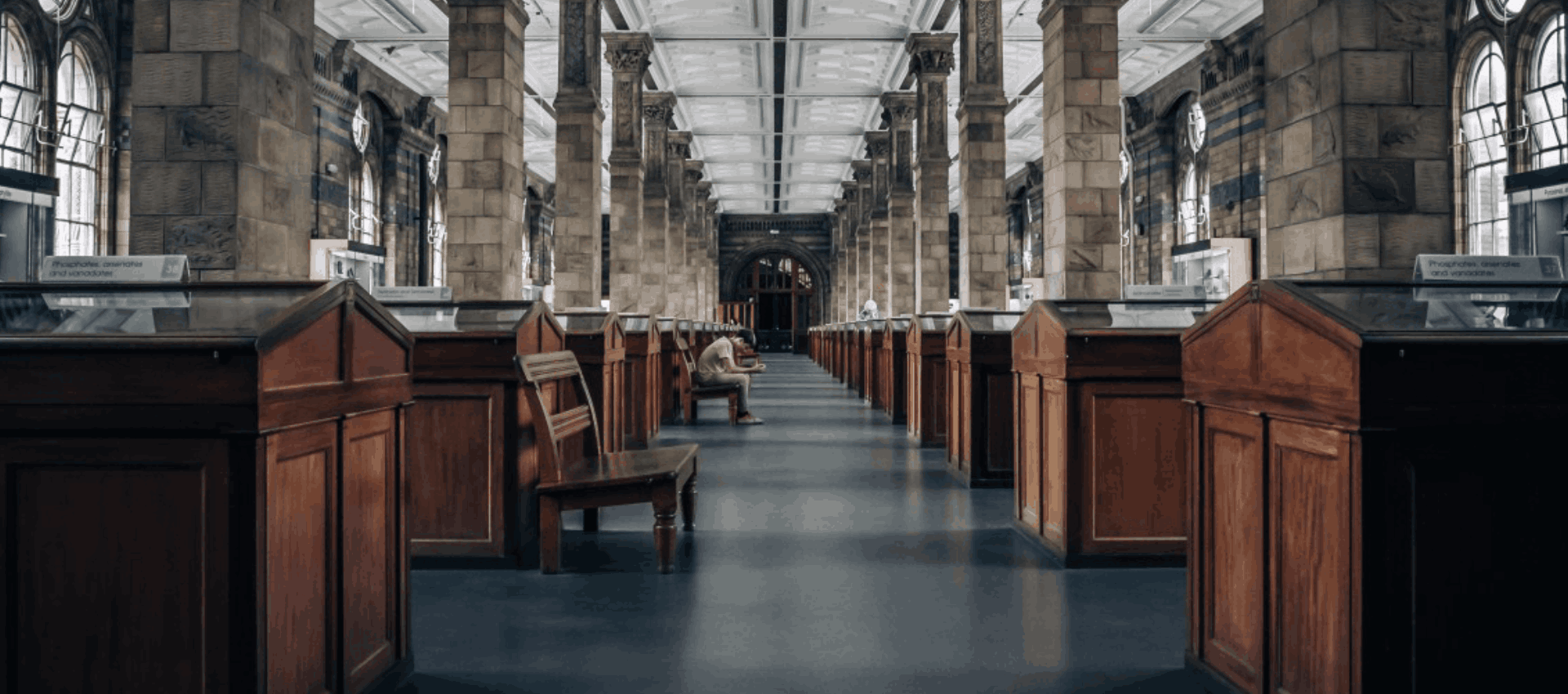

DARLINGHURST GAOL.

This prison is situate on the site of Woolloomooloo Stockade, and was erected for Imperial convicts, who quarried and cut the stone and partly built the outer walls. Two wings and principal gaoler’s quarters were built by free labour during 1840, when, in consequence of the great destitution among the working classes, the Government found it necessary to employ s number of mechanics upon work which was not then absolutely required.

Bird’s eye view of Darlinghurst gaol. Source: Illustrated Sydney News, Fri 16 Nov 1866, p. 76. Reproduction: Peter de Waal

On 7th June, 1841, the prisoners were transferred from the old gaol in George-street to Darlinghurst, the prison then consisting of the north and south wings only—the present walls enclosing the stockade as well as the prison—admission to the stockade being obtained through a gateway on the eastern wall; this gateway has been for some years closed up; though until very lately the eastern part of the enclosure has been known in the prison as ‘The Stockade.’ The prison now consists of four wings on the radiating principle, the fourth having been erected wholly by prison labour. Debtors’ prison, with principal warders’ quarters, hospital, bath house, workshops, the stone for these buildings, as well as for the division walls to yards, has been cut by prisoners. The buildings have been put up mostly by free labour.

The north or trial A wing, on ground floor, 24 single cells, each 8 x 5 x 10 ft high;

middle and top landings, 24 large cells, each12 x 2 x10 ft high. North-east, labour or B wing,42 cells, 12 x 8 x 10 ft high. South-east , new or C wing, 78 single cells, each 8x 5 x 10 ft high, and 6 cells, 8 x 5 x 10 ft high. In all 102 large cells, calculated to accommodate 3 prisoners each, and 108 single; that is, accommodation for 414 prisoners.

Two of the large cellos are padded for lunatics, others are used as stores; so that the actual room in the gaol is for 400 prisoners, without allowing for casualties or unequal division of classes.

The hospital, 1 ward, 25 x 24 x 12 ft high, room of 8 beds in each, for males. For females—1 ward, 25 x 22 x 12 ft high, 10 beds.

Debtors’ prison, ground floor 4 sleeping cells, each 12 x 8 x 11 ft high; upstairs 2 sleeping cells 12 x 8 x 13 ft high; and common room 22 x 18 x 13 ft high.

The old yard contains 3¼ acres, and the new one, 1¼ acre; the whole surrounded by a strong wall 20 feet high.

Number of prisoners—Daily average the last five years:—1861 – 310; 1862 – 320; 1863 – 375; 1864 – 437; 1865 – 475.

Greatest number at any one time:—1861 – 419; 1862 – 436; 1863 – 480; 1864 – 495; 1865 – 548.

Total number received during 1865: For trial, males 190, females 47, total 237; examination, males 168, females 44, total 212; in transit, males 62, females 27, total 89. Under sentence: Labour, males 590, females 93, total 683; imprisonment only, males 1117, females 1123, total 2240; debtors, males 38, females 3, total 41. Of this number there have come into gaol: More than once, males 236, females 98, total 334; more than twice, males 87, females 38, total 125; more than thrice, males 163, females 295, total 458. Many, particularly women have been admitted as often as 15 or 16 times during the year, some more frequently.

Employment consists of stone cutting for building purposes, mat making and weaving, tailoring, shoemaking, bookbinding; carpenters, painters, smiths, and coopers are employed at their trades. Expert mechanics are very few, and difficulty is met with in providing employment for so many men having no knowledge of the use of tools.

In August, 1865, an overseer of trades was appointed to superintend the work of tailors, shoemakers, and bookbinders. A number of men have been successfully employed making shoes and clothing for prison use. Previous to August but 2 tailors and 2 shoemakers were at work mending prisoners’ clothing. From August to end of the year the numbers employed averaged—tailors, 13; shoemakers, 17; these men earned £750. Deducting from that the cost of material and salaries of overseers that left a clear profit of £300 in the four months; since then their labour has been of equal if not of more value. One thousand pairs of shoes have been made from August to present time, at a cost for material of about 2s 3d per pair; these shoes cost by contract 5s 3d per pair. The making of clothing is not so profitable, in consequence of the high prices to be paid for material. Grey cloth for winter wear cannot be had in Sydney.

Return of value of labour during 1865 estimated at £6700, principally earned by stonecutters, who cut 33,026 feet of stone; by matmakers, who made 1023 door mats; weavers, who made 4000 yards matting.

It must be borne in mind that nearly all the men at wok have to be taught.

Hours of labour from 7 to 8, 9, to 12, and 1 to 4; in all, 7 hours. A great many attend school; some one hour, others two hours, thereby reducing the hours of labour one and two hours daily.

Too much credit cannot be given to Mr Read, the present Governor of the Gaol for his philanthropic efforts to better the condition of the prisoners by teaching them trades that will afford an honest livelihood when their sentences have expired, and also for his attempt to solve the problem of how to make prisoners support themselves. The workshops are situated in the building which runs across the top of illustration No. 1, on the upper floor of which, on the occasion of our visit found Gardiner (the bushranger) and other notorious criminals busy making mats, and in an adjoining room, weaving matting, was an unfortunate young man who owes his loss of liberty to the temptations of Gardiner and Gilbert. No time seems to be wasted, no conversation permitted, or anything that would divert attention. The store contained piles of matting, mats, and other manufactures, some of which have since found their way to the Intercolonial Exhibition.

~ ~ ~ ~ ~

The Sydney Morning Herald, Mon 8 Mar 1886 [3]

DARLINGHURST GAOL.

———◦———

(By Our Own Reporter.)

———

Darlinghurst gaol and courthouse, in foreground, complex, c. 1930. SRNSW NRS4346, Photographs of NSW Public Buildings c. 1880-1940, photo 8020

The position of Darlinghurst Gaol is well known, and the prison forms a conspicuous object to persons travelling along the eastern tramline near where Botany-street branches off from Oxford-street. It covers an area of about 4¾ acres, and is situated on about the highest point of a ridge having between it and Oxford-street the Darlinghurst Courthouse, with the large plot of tree-planted land in front. At the back, but divided from it by a wide street, and situated on the slope of the hill, are the School of Industry with its extensive grounds, and the Green Park, where there is a good growth of shrubbery and trees. The northerly boundary is formed by Burton-street, a fairly wide road; and on this side, also at right angles to Burton-street, and running along the backbone of the ridge, is Little Dowling-street, a wide roadway terminating at Burton-street, or, speaking more accurately, at the gaol wall. This cross street has the effect of throwing the gaol open to winds from a northerly direction. The remaining boundary is formed by a roadway which may be termed a curved continuation of Forbes-street, carrying the traffic to the point at Darlinghurst where Bourke, Forbes, Oxford, and Botany streets intersect. Opposite the gaol gate is the reception house for the insane, situated on a triangular piece of land, sloping considerably from the gaol. This triangular block may be said to have Burton-street for a base, and Forbes and Bourke streets respectively for the sides, the point being towards Oxford-street, but terminating at a considerable distance from that street, leaving a large open space formed by the conjunction of Forbes and Bourke streets. On the point of this triangle the Darlinghurst police station [4] is situated. The reception house is nearly directly opposite the gaol gates, the rest of the triangle being planted with tress, shrubbery, &c. the site of Darlinghurst gaol is in the centre of a populous district, but from the foregoing description of its boundaries it will be seen that the block is isolated. Only upon one side of it, namely Burton-street, are there any residences near. The position of the gaol is commanding, it is open to the prevailing winds, and its elevation is advantageous in respect of the matter of drainage and sewerage. The drains are all connected with the sewers running into Woolloomooloo Bay, and one proof that they are adequate is the fact that they carry off all stormwater, which at times is extraordinarily heavy. The area of the prison is drained and trapped, the closets all flushed with water on the principle in vogue in Sydney, and should any pipe become choked it is immediately cleaned by prisoners specially told off for the work, these men receiving in consideration an extra ration of tea, sugar, and tobacco—a privilege the value of which they highly esteem. Water is supplied from the Woollahra and Paddington reservoirs, and during the late intermittent supply to the city, very properly the gaol had a continuous water supply. On some former occasions when the intermittent system was applied to the city, it was applied to the gaol also; but the inconvenience and danger to health where so many persons were crowded together were so great that it could not be tolerated, and accordingly arrangements had to be made for a continuous supply at all times. There is water stored in wells within the gaol itself, but this could not be utilised for all purposes, where the demands are so excessive.

Darlinghurst police station con structed 1899. Photo: Peter de Waal

Darlinghurst gaol chapel. Photo: Peter de Waal

Before leaving the subject of water, we may mention that in case of an outbreak of fire there is a fire engine in the gaol; and in the workshops, which one would think the only place, except the governor’s and officers’ quarters, at all liable to an outbreak of fire, there are water pipes running along in branches, each branch nearly meeting the other, and capable of being rapidly connected. The central building in the gaol block is the church, the “wings” containing the cells radiating from it, but allowing a considerable space between it and the wings. These wings are built in three flats or stories, with corridors running the whole length, the cells being situated on either side, and for the better internal working these wings are designated A, B, and so on. The yards belonging to the wings are like so many segments of a circle, this form being caused by the large oblong buildings radiating, as already said, from one centre, and they are distinguished by numbers. The A wing, or the “trial wing,” as it is termed, contains 24 “associated” cells. These cells are each 12 feet x 8 feet by 10 feet high, each containing three hammocks, which are swung at night, but rolled up during the day. There are likewise 22 single cells, each of these being 8 feet x 5 feet, and 10 feet high. Ventilation is secured by a small ventilator coming through the wall from outside, and also by two windows placed high up in the “associated” cells; that in the “single” cells is by means of a similar ventilator through the wall, with a single window above. This wing is occupied by men awaiting trial, by prisoners on remand, by men awaiting transit to other prisons, and by hard labour men.Darlinghurst gaol floor plan. Photo: Peter de Waal

The transit and remanded men are allowed out during two hours in the day for exercise in the yard, the rest of the men for the rest of the day. The different classes take their meals separately, and in this way the classification is preserved. The yard is flagged over the whole area, and along one side and for the whole length is the mess-shed, with table, on which the men take their meals. Against the wall of the wing are pigeon-holes of wood, used by the prisoners as cupboards. One side of each yard is formed by one of the walls of a prison “wing,” the other side by the division between it and another yard, the ends being protected by lofty iron railings, at the gate entrance to which stand the warders. At the most remote part of the yard are situated the lavatories, closets, &c, all of which are connected with the water supply and sewerage systems. The accommodation in this wing is for nearly 100 men, and there were 82 at the time of my visit. Most of the prisoners are engaged at the workshops all day, in connection with which there is the necessary sanitary accommodation. These yards are all so placed that they get a good share of sunlight, besides which each one is well drained, trapped, and cleaned out and disinfected with carbolic acid every morning. The B wing or the “observation ward,” as it is called, is the place where men who are supposed to be insane, or who are suffering from delirium tremens, are kept, subject to medical supervision, the basement being used for this purpose. The cells in this special compartment are different to others, inasmuch as they are fitted with an inner and outer door, so that either one or both can be shut. When a man is suffering from delirium tremens, he often feels a suffocating sensation, and in his case only the grating or inner door is closed; or during hot weather this door only is closed, much to the advantage of the prisoner. The cell, otherwise, is ventilated in a similar manner to the one already described. Each “observation” cell is fitted with a porthole, which admits the light from above, and lower down there is a smaller porthole with a piece of glass fitted in, be means of which the attendant is able to look on unobserved and see what the patient is doing. The senior officer and two men visit this portion of the prison three times every night. Their visit may be at 9.30 pm, 1.30 am, and 3.30 am; they vary the time, but generally maintain the interval shown. An officer is always on watch at the entrance to the corridor, and if a prisoner knocks at his cell door or there is any unusual sound he reports it. The men in the observation ward do not sleep in hammocks like other prisoners, but on the floor, a thick fibre mat being first spread out, and then a mattrass [sic] placed on the top. There is one padded cell in the corridor for violent cases, the unfortunate prisoner having leather “muffs,” which is considered much more humane than the straight waistcoat. The “muffs” are so made that the hands do not lie together, but each one fits into a single compartment, so that it is impossible for the wearer to scratch or tear his hands, and the muff is so fastened that he cannot withdraw is hands. Placed in the padded cell he can rush or knock himself without injury. For less violent cases there is a boarded cell. It is said that of the cases received in this ward which terminate fatally, most of the deaths occur during the first fortnight of their detention. The middle and top landings of this wing comprise 14 associated cells on each, occupied by hard labour men. The yard attached to this wing has the usual mess shed running along its whole length. There are also the lavatory and three closets &c. There were altogether 84 men quartered in this wing, the capacity under the present system of “associated” cells being nearly 100. During the absence of the hard labour men the “observation” men are allowed to exercise in the yard, returning to the wing before the labourers come back. The closet accommodation would appear wholly inadequate for such a number, but it must be remembered that the bulk of the men, the hard labour prisoners, are away during the day, and that necessary sanitary accommodation is provided where they are at work. The other wings are on the same principle as A, but B wing is the only one used for observation cases. Some of these wings are larger than others with a greater number of cells, as in the case of C and E wings. On the occasion of my visit there were nominally 345 men in the E wing, which on the associated principle has accommodation for upwards of 300 prisoners (putting three together in one cell), but only 318 slept in the wing, the remaining twenty-seven being quartered in the schoolroom.Darlinghurst gaol entrance gate. Photo ID: SRNSW 4481_a026_ 000669.jpg

There are various yards designated by numbers instead of letters, and in these the classification of the prisoners is carried out as far as practicable, but the number of the prisoners has caused difficulty in this matter. It is considered desirable to keep the different classes of prisoners apart. Thus one yard is devoted to those who have been convicted only once, another yard to twice-convicted men, and habitual criminals are kept together. Yard No 4 is for boys under 20 years of age, and these youths are kept apart from the other prisoners by being placed in a portion of the works by themselves picking oakum. A warder is put over them to prevent them holding communication with the other prisoners, but the isolation must be unsatisfactory, even supposing it to be carried out, for to all intents and purposes these lads are with the other confinees, except in the matter of speech. No 10 yard contains what are termed the “confinees,” that is, those who are in prison in lieu of paying fines. These prisoners are supplied with food by their friends from outside the gaol, and if the food is not brought they are made to work, and, of course, are fed on prison diet. Yard No 5 contained a number of men of the low vagrant type, serving sentences of from seven days up to twelve months, for minor offences, but not sentenced to hard labour. There are at present four boys in Darlinghurst from about 10 years of age to 13, one of them being at present in the hospital. The three smaller ones were sentenced for stealing from a dwelling in Parramatta, and these lads—mere children in fact—are kept by the Judge’s orders apart from the other prisoners. The youngest of them do not appear to comprehend the seriousness of their offence, or to feel the punishment as it was hoped they would do. The prisoners sentenced to hard labour are occupied in the way they can be made most useful. Stonemasons, builders, carpenters, and that class of workmen are engaged upon such works within the gaol as the erection of the new hospital, a building of two storeys 60ft x 25ft, with corridors and balconies. The height of the roof on the lower floor is 15 feet, the ceiling being built in concrete arches. Each floor is to be fitted with 11 beds, and the bathing and other accommodation is to be in accordance with the best designed of such institutions, and in keeping with the building which is being fitted with all the latest hygienic improvements. The portion of the new hospital will be ready for occupation in a few weeks’ time, when the old structure will be pulled down, the remaining portion of the new one to be erected on its site. The hospital, when completed, will accommodate about 40 patient. In another portion of the gaol enclosure a small iron hospital has been erected by the prisoners on the principle of the Little Bay Coast Hospital, with accommodation for four patients. It may also be mentioned that there are several hospital tents erected within the gaol should any emergency arise. The mortuary is placed at the rear of E wing, and the sulphur-house at the rear of that again, the latter being used for fumigating the filthy clothing of some of the prisoners on their entrance to prison.

To return to the employments of the prisoners. Some six of them are engaged in brush-making, four are in the paint-shop mixing paints, &c, but by far the larger number are in the mat-making room, where about 100 men are engaged. The mat-making shops are long rooms altogether too little ventilated for the carrying out of such an industry. The severest commentary on this department is the statement that the majority of hospital cases come from it. Seven prisoners are engaged in book-binding. There are 21 shoemakers who make boots and shoes for the us of prisoners, warders, and inmates of asylums. In the tailoring department there are some 20 men engaged in making prison clothing, and for the use of the inmates of orphan schools, &c. Seven men are in the tin-workers’ shop, and 10 at the blacksmithing. The hard-labour prisoners in the workshops have a certain task to perform, the working hours being from 8 till 12 o’clock and from 1 until 4 o’clock in the afternoon, the hour’s intermission being for dinner. For all work done over their allotted task they are allowed a bonus, which they receive on leaving gaol.

Early women’s Darlinghurst gaol cell block plaque. Photo: Peter de Waal

Former D wing, now the cell block theatre. Photo: Peter de Waal

The female prisoners are confined in C and D wings, where there has been equal overcrowding. These wings are exactly similar to those in the other part of the gaol, the principle of associated cells being carried out. The matron, to meet cases, had a number of bedsteads placed in the corridor of C wing, where as many as 22 women slept. This relieved the cells, no doubt, but it vitiated, to a certain extent, one of the sources from which the supply of air to the cells is derived, although it must be regarded as an improvement on placing four prisoners in one cell. There is a large room, where the women are engaged on allotted tasks on needlework, but they are allowed, after completing their tasks, to do needlework—such as fancy work—for persons outside the gaol. The classification of the female prisoners, like that of the males, is carried out in the yards, one yard being used for the younger prisoners, another for those with fewer convictions, and so on, the yards being provided with watch-boxes for the female warders. The hospital for the women is under a trained nurse, and excites the commendation of every visitor by its cleanness and the order which prevails. It is furnished with 15 beds, four of which are in an isolated ward. For both males and females there are baths—13 for the males, and four for the females—fitted with hot and cold water taps and showers. The hot water is supplied from a horizontal boiler. There are baths for the warders, which are also used by the debtors who may be under confinement. The kitchen for the whole of the gaol is fitted with steam cooking apparatus, on a similar principle to that used at Callan Park Asylum. There is a shed for clothes washing, and a steam-heated laundry for drying. On the occasion of my visit the cells and yards were all alike beautifully sweet, and clean as a new pin. The officers of the prison cannot be held responsible for the overcrowding, but they certainly can for cleanliness, and in this respect they appear to be fully alive to their duty. Not only was the prison clean, but there was an entire absence of bad smell from the drains or other places. At the time of my visit the doors of the unoccupied cells were open, so that there was a good current of air through them. But it must be a somewhat different thing when the cell door is closed and the air becomes vitiated by the breath of the occupant, as it must do to a certain extent. The want of pure air must be felt mostly in the associated cells where there are three men, and in which the necessary evil of the night tub must almost be enough to breed pestilence. This evil must exist in every prison, but is not necessarily so great in the case of single cells. A partial remedy might be found by making double doors to all the cells, as in the case of the “observation” cells, the inner door being a grating so that either door could be closed at the wish of the prisoners. The spiritual well-being of the prisoners is well looked after. The church is fitted with a gallery when [sic] the women sit, the men beneath, but neither can see the other, although both can see the officiating minister. There is service for Roman Catholics, Church of England, Presbyterians, and Wesleyans, on Sundays. On Wednesdays there is a service for Presbyterians; on Thursday for Church of England; the Bethel Union minister holds service on Friday; the Sisters of Mercy have a service on Thursday forenoon, and the Wesleyans on Thursday afternoon. There is a Hebrew service on Saturday and a Roman Catholic service on the same day. In addition, a Chinese minister occasionally visits the prison, and there is also a choir practice.

To maintain discipline there are 26 warders on day duty, and 11 on night duty, the latter in two watches of four each, and three men in addition on duty all night as a reserve, besides the senior warder. The warders all parade at 6 o’clock in the morning, continuing on duty until 6 o’clock at night without any relief for meals, which are taken whenever a chance offers. The men for night duty fall in at 4.45 pm under arms as a guard, and the first watch goes on duty from 4.45 pm until half-past 10 at night, without any intermission for tea. The men of the second watch go on from 4.45 till about 6 o’clock, remaining off until half-past 10, when they return to duty and remain on till 6 the next morning without any relief. At the first and second gate two men stop on from 4.45 pm till 6 o’clock the next morning, but the first gateman can go into the reserve-room at 10.30 pm, and sleep until 6 o’clock next morning, unless called up for duty; the second gateman can rest from 6 o’clock pm until 10.30 pm, when he has to take the post of first gateman the remainder of the watch. There is what is termed “reserve duty” done by the ordinary men. This duty consists in going on duty at 6 o’clock and remaining on for 24 hours continuously; they are then allowed off for the next 24 hours. The men do this duty in turn, which comes round about three times in a month. The warders are evidently the hardest-worked men in the prison, doing from 12 to 13 hours per day. The men on the watch-towers are armed, and maintain a continuous watch over the prison, without any relief for meals. Whenever one of them goes in from his tower he hangs out a red flag, and so long as that remains out the warder in the tower to his right and left have to remain on the alert. The warders in the prison yard are always unarmed, but in case of any disturbance the men are supposed to rush to the gate and get under arms. These are the means adopted for maintaining discipline so far as the warders are concerned; but the number of these men appears to be inadequate for the work. It is said that 20 years ago there were as many warders as to-day, although, owing to visitors to the workshops, and the largely increased numbers of visitors to prisoners, all of whom have to be accompanied by a warder when in gaol, the work has been very greatly increased.

Discipline is maintained amongst the prisoners by prompt punishment should any of them be found trafficing [sic] with each other, or if found with prohibited articles. It is also an offence for a prisoner to enter any other than the yard to which he has been assigned, or to speak to any prisoner of a different classification, or for singing at night in his cell, destroying Government property, or for any breach of the regulations. The visiting magistrate attends the gaol twice a week, and hears the charges; the punishments awarded, according to the offence, may be imprisonment in the dark cells, or flogging, which is administered with the “cat,” and in the case of boys with a leathern thong.

The prisoners are subject to “ordinary” and “separate” treatment, Berrima gaol being known as the “separate treatment gaol.” No prisoner undergoing less than three years is put under separate treatment, unless it has been specially ordered. A man sentenced to three years has to undergo separate treatment for the first nine months of his sentence, and for the remainder of his sentence he goes into the C Division for ordinary treatment. A prisoner under sentence of five years has to undergo separate treatment for the first nine months. He is then passed into the B division till half his sentence has expired. While in this division he is locked up every Saturday afternoon, every Sunday, and all holidays. The remainder of his sentence he does in the C division under ordinary treatment.

The overcrowding of Darlinghurst gaol has rendered the classification very difficult, there being a lack of room in the yards although the classification system has been followed out as closely as possible under the circumstances. The first-time prisoners are supposed to have yards to themselves, and if there should be only two such prisoners, they have a yard separate from the more hardened and habitual criminals. It is found impossible in the overcrowded state of the gaol. Darlinghurst gaol was intended for the accommodation of 650 persons—namely, 500 males and 150 females—but latterly this number has been greatly exceeded. The largest number in this gaol at any one time was 947 prisoners, on August 1, 1884. During this year the numbers have been on certain dates as follows:—January 3, 786; January 9, 823, January 15, 859; February 3, 846; February 4, 850; February 12, 837; February 15, 855; February 17, 857. On Friday last, the 5th instant, there were 773, the decrease being accounted for by the numbers despatched to the country gaols. The average number of prisoners under penal servitude is increasing under the operation of the new Act. During the year 1885 there were 12,424 prisoners in Darlinghurst gaol, of whom 14 males and seven females died. The average number of cases in the hospital was about 30, and about the same number received hospital fare.

Hard-labour prisoners are allowed to write once in three months to a friend, and once in six weeks to a parent, wife, or child; and to receive a letter from a friend once in every six weeks, and from a parent, wife, or child once every three weeks. “Confined” prisoners are allowed to write monthly and to receive letters fortnightly. A prisoner awaiting trial writes as often as he chooses. A prisoner may write special letters by permission, but that does not interfere with his ordinary writing. It is a fortunate thing, and speaks much for the excellent management of such an institution, that no fatal epidemic has broken out within its precincts; and the possibility of such a catastrophe, which would be fraught with danger to a populous portion of the city, ought to lead the authorities to adopt such measures as will abate existing evils, and enable to prison to be conducted safely.

~ ~ ~ ~ ~

Australian Town and Country Journal, Sat 21 Oct 1899 [5]

DARLINGHURST GAOL.

————

Darlinghurst gaol: 1. Entrance. 2. Muster on arrival. 3. Inquiry office. 4. Selecting boots. 5. Bookbinding shop. 6. Cell interior. 7. In church. 8. Night watch. 9. Prisoners’ yard. Image: Australian Town and Country Journal, Sat 21 Oct 1899, p. 32. Reproduction: Peter de Waal

Darlinghurst Gaol, the great metropolitan prison, dates from the thirties. The sum of £10,000 was voted by the Council in 1839 for its erection, and it was first occupied by prisoners on June 7, 1841. At present it accommodates about 400 prisoners. Last year 6034 were received, being 5036 males and 998 females. Discharges and transfers accounted for 5073 males and 1021 females, leaving 384 males and 18 females in the gaol. The labor of prisoners is turned to good account, as may be seen by the number of industries carried on. Boot-making and bookbinding have recently been transferred to Parramatta Gaol, it being found that the concentration of trades gives better results. In Darlinghurst the following trades are carried on; Blacksmithing, brush making, carpentry, mat-making, needlework, painting, printing, tailoring, tinsmithing, turnery, upholstery, etc. The total value of the labor for 1898 was estimated at £10,365 9s 4d. The total value for all the gaols of the colony for last year was estimated at £44,818. It is gratifying to note that the supply of such labor has been steadily decreasing for twenty years, if compared with the increase of population. In 1898 658 prisoners were received in the gaols under sentence from the higher courts, as compared with 792 during the preceding year, a decrease of 134. The rate per 100,000 of the community was 59.6 for 1897, as compared with 48.6 for 1898, a drop of 11. It has been generally agreed by the authorities that the increase or decrease of crime in a community may fairly be gauged by comparing the number of persons convicted of indictable offences with the general population. The decrease in such convictions during the last twenty years has been continuous, and it has been especially marked of late years, the number for 1898 being actually less than for 1878, while the general population has nearly doubled.

[1]1 The Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser, Thu 10 Jun 1841, p. 4 Thu 10 Jun 1841, p. 4 ” f D. Emphasis added.

[2]2 Illustrated Sydney News, Fri 16 Nov 1866, pp. 76-7 Fri 16 Nov 1866, pp. 76-7 ” f D.

[3]3 The Sydney Morning Herald, Mon 8 Mar 1886, p. 6 Mon 8 Mar 1886, p. 6 ” f D.

[4]4 The nucleus of the present building was constructed in 1899, by WL Vernon, NSW Government Architect, at a cost £3,000.00. It was built on the site of the 1850s Darlinghurst watch house. A court for centralising lunacy was established in the building. Two additional cells were built in 1930 and in 1935 an upper floor was added to the former single story side wings. Major remodelling was made to the station in 1955-6.

[5]5 Australian Town and Country Journal, Sat 21 Oct 1899, p. 38.

Leave a Reply